Followers of the Vorkosigan Reread have known for a long time that Bujold’s works are inspirational in any number of ways. At least, I assume that’s why they’re following the reread. Last week, the Vorkosigan Series became one of the first ever to be nominated for a Best Series Hugo, and this week an article in Nature is describing work at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Research Institute on the development of a uterus-like life support system for premature infants! Bujold’s uterine replicator has played a major role in shaping the worlds of her books. It allowed for the creation of the Quaddies, and for their enslavement. It allows the all-male population of Athos to produce their precious and beloved children. It offered an alternative to abortion for Prince Serg’s victims. It lets the Star Creche on Cetaganda control reproduction without controlling interpersonal relationships. It lets Betan and Barrayaran mothers pursue dangerous careers in fields like space exploration and politics while their infants safely gestate in a controlled environment. And that’s just for starters. How close are we to developing a uterine replicator? Closer than we were!

Which is to say, not close!

The popular media is horrible at reporting scientific news. Headlines are sensationalized, and conclusions are misinterpreted to ensure maximum page views without adequate or thoughtful scrutiny. Remember all the articles about how dark chocolate helps you lose weight? Remember how actually dark chocolate does nothing of the sort? Bad science reporting is bad, and no one should do it. News headlines about this new device have used the term “artificial womb,” and that’s a little irresponsible. The language being used in the journal article is “extra-uterine system to physiologically support the extreme premature lamb” or “biobag.”

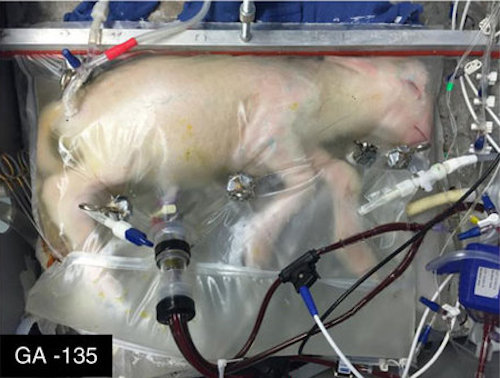

What we have below is a lamb in a bag—it looks like you could tuck a little curry powder and some sprigs of mint in there and have Sunday dinner. It uses a pump that is powered by the lamb’s heartbeat to exchange blood through an oxygenator. A separate pump system handles amniotic fluid input and output. The device has been used to support prematurely delivered lambs for up to four weeks. Lambs grow in the bag. Some have survived delivery from the bag. One lamb has reached a year in age and had a normal brain MRI. Don’t get too excited about that—it just means that this particular lamb had normal brain structures; it’s difficult to evaluate neurological functioning in sheep.

The researchers on the project have described efforts to create a womb-like atmosphere by maintaining the biobag at normal sheep body temperature, keeping the biobag in a dimly lit room, and playing recordings of a sheep heartbeat to the lamb. They have also suggested measures that would facilitate parental bonding, like a video monitoring system that parents could access. Watching a livestream of a lamb isn’t going to benefit a mother sheep; the research team is clearly thinking hard about human applications. The long-term goal of the project is to provide an alternative to NICU care for extremely premature infants, and to improve outcomes for these infants by allowing them more time to grow in uterine-like conditions following cesarean delivery. One obstacle in the path of this goal—and a good one!—is that NICU care already does a pretty good job. Although there are a great many challenges in the field, and NICU care is not a substitute for time in utero, the effectiveness of current approaches to neonatal medicine create a pretty high bar for any experimental device to clear before it can be considered as an alternative to current approaches to care for premature (and even extremely premature) infants.

The authors of the study assert that they are not trying to extend the currently known limits of fetal viability. The biobag also won’t be used to address maternal risks in pregnancy until it’s undergone a great deal more testing and development; it’s not a good enough substitute for the human uterus to justify elective premature delivery before the development of a life-threatening crisis for mother or fetus. And certainly, the device that these researchers have created won’t make Betan-style, grab-a-few-cells-and-shove-them-in-a-replicator reproduction possible; the biobag requires that the fetus have an umbilical cord. The research team over at CHOP has ambitious plans. As a lay observer, I anticipate that the reality will involve years of animal studies before these plans reach fruition.

You know what, though? This is really cool. The place we’re in now, at the beginning of this very long scientific process, is a lot closer to making the uterine replicator—and hopefully just its benefits, not its ethically problematic drawbacks—into a reality.

Ellen Cheeseman-Meyer teaches history and reads a lot.